Mississippi Blues Trail Series – McComb: Summit Street and Bo Diddley

An Article by Brenda Germany

Photos by Stephen Anderson

Additional photos by Brenda Germany

Nestled in the lush rolling landscape of Pike County in southwest Mississippi, the city of McComb lies just above the Louisiana state line. Its advantageous location of 100 miles north of New Orleans, 80 miles from Jackson, and 75 miles from Hattiesburg made it the perfect choice for Colonel H. S. McComb, President of the New Orleans, Jackson and Great Northern Railroad Company. His plan to relocate the railroad company offices, maintenance shops and workers to an area that would allow for expansion and provide distance from the tempting attractions of New Orleans’ night life came to fruition when he purchased and consolidated the three nearby communities of Elizabethtown, Burglund, and Harveytown, to form McComb in 1872.

Although the railroad was the primary driving factor in McComb’s economy, the McComb Ice House and Creamery was deemed the south’s largest ice house in 1924, producing more than 200 tons of ice per day. Working hand in hand, these two companies developed extensive processes of shipping southern produce and perishable items to northern parts of the country further expanding the prosperity of McComb and the railroad exponentially.

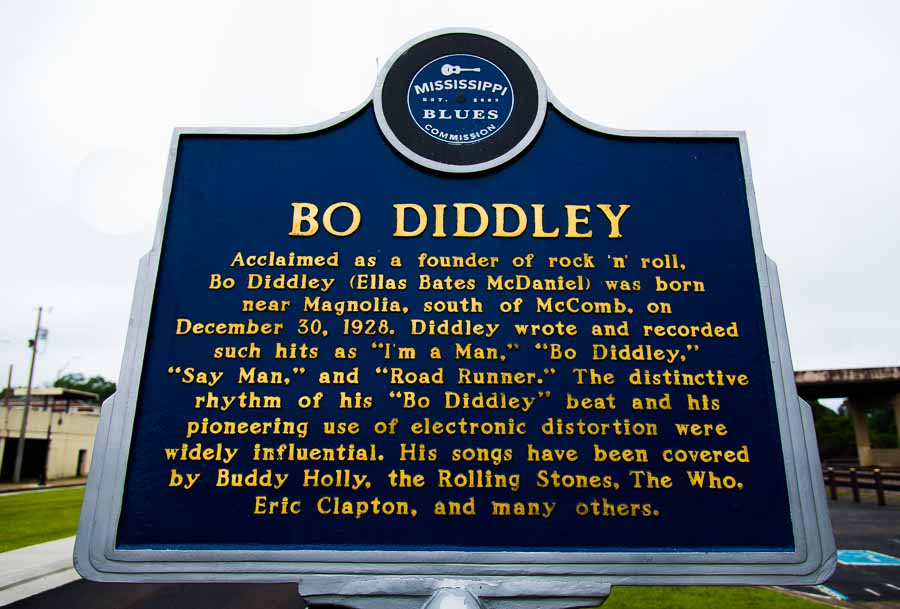

Top photo: Bo Diddley Blues Trail Marker in McComb, MS (photo by Stephen Anderson); Above photo: The McComb City Railroad Depot Museum in McComb, MS (Photo by Brenda Germany)

Top photo: Bo Diddley Blues Trail Marker in McComb, MS (photo by Stephen Anderson); Above photo: The McComb City Railroad Depot Museum in McComb, MS (Photo by Brenda Germany)

The railroad which evolved to first become the Illinois Central Railroad and currently the Canadian National Railroad is still important to McComb today with its mainline still running through the heart of the city. The Amtrak station now continues to provide access to New Orleans and Chicago through its famed City of New Orleans line. As a tribute to the historic beginnings of the city its attractions include the McComb City Railroad Depot Museum housing a collection of 1,500 railroad artifacts and authentic full size rail cars that tell the story of this town.

Also playing a large part in the history of McComb is its contribution to the development of blues, jazz, rhythm and blues and rock and roll through the many talented musicians that called it home. Commemorating that contribution, the Mississippi Blues Commission placed two Blues Trail markers in the city of McComb: Summit Street and Bo Diddley.

Summit Street Blues Trail Marker in McComb, MS (photo by Stephen Anderson)

Summit Street Blues Trail Marker in McComb, MS (photo by Stephen Anderson)

Summit Street

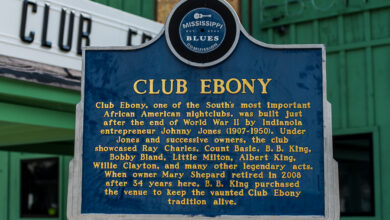

From its beginning as a city built around the growing railroad industry, McComb flourished, serving as a vital lifeline for the many industries attracted to the region. One particularly well-known area of McComb that prospered after the railroad’s expansion was Summit Street. It gave life to the African American owned businesses, night clubs and cafés located there but, especially, to the musical development and evolution taking place from the 1900’s to the 1960’s. It was also the time period in which the Chitlin Circuit began to emerge. This collection of black only performance venues allowed black musicians and entertainers the opportunity during segregation to earn a living by doing what they loved. Summit Street was a thriving African American business district as well as a hotbed of musical activity. Blues, jazz, and rhythm & blues bands entertained at various nightclubs, cafes, and hotels, and many musicians lived nearby.

Chitlin Circuit locations were clustered along the major North-South corridor (Chicago-New Orleans route) and East-West corridor (Meridian-Vicksburg route). Among the Mississippi venues were Canton’s Blue Garden Night Club–later rebuilt as the New Club Desire; Columbus’ Queen City Hotel; McComb’s DeSoto Hotel and Club, Harlem Nightingale (later Elk Rest Club), Brock’s Mocombo, and Club Rockett; Elks Hart Lodge #640, Greenwood; Club Ebony, Indianola; Ruby’s Nite Spot, Leland; Rhythm Club, Natchez; Blue Room, Vicksburg, Rankin Auditorium, Fannin Road ‘cross the river’ from Jackson, Harlem Inn, Winstonville; Stevens Rose Room, Jackson, Hi-Hat Club, Hattiesburg and The Elks, Greenville.

In the heyday of Summit Street, recalled local businessman Bennie Joseph, “People come from all over to McComb, from Chicago all the way to New Orleans, man. It was a wide open city. They had clubs, gambling, corn liquor, everything . . . Dancing, partying, drinking.” As the primary stop on the Chitlin Circuit between Jackson and New Orleans, McComb drew national talent such as B. B. King, John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Roy Brown, Ivory Joe Hunter, Solomon Burke, Marvin Gaye, Little Milton, Bobby Rush, Archie Bell & the Drells, Lucky Millinder, Ray Charles, Fats Domino, Dave Bartholomew, Lloyd Price, Roy Milton, The Bar-Kays, Groove Holmes, Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong, Redd Foxx, and McComb’s most famous native, Bo Diddley.

The McComb area’s impressive musical roster also includes Vasti Jackson, Robert “The Duke” Tillman, Larry Addison, Randy Williams, Fread Eugene Martin (aka Little Freddie King) and his father, Jesse James Martin, Zebedee Lee, Brandy Norwood, Omar Kent Dykes, Steve Blailock, Charlie Braxton, Ric E. Bluez, Reverend Charlie Jackson, Bernard “Bunny” Williams, Pete Allen, Chainsaw Dupont, Johnny Gilmore, Robert Rembert, John Lee Allen (“Tater Boy”), vocal group singers Prentiss Barnes of the Moonglows, Robert “Squirrel” Lester of the Chi-Lites, and Leon “Pop” Williams, founder of the Williams Brothers gospel group. The area was also an active center for blues pianists in the 1920s and ‘30s, according to piano legend Little Brother Montgomery, and McComb reportedly was at one time the home of early blues and gospel recording artists King Solomon Hill (Joe Holmes), Cryin’ Sam Collins, and the Graves brothers, Roosevelt and Uaroy. In McComb and many other cities, commerce in areas such as Summit Street began to decline when much of the African American trade dispersed to other parts of town after the coming of integration in the 1960s.

Bo Diddley Blues Trail Marker in McComb, MS (photo by Stephen Anderson)

Bo Diddley Blues Trail Marker in McComb, MS (photo by Stephen Anderson)

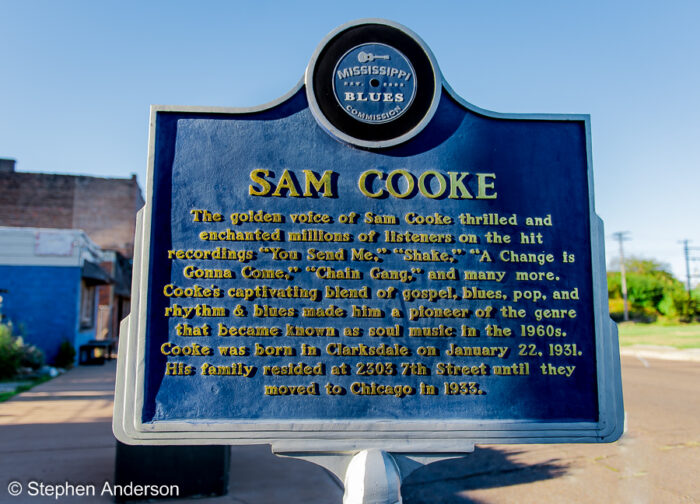

Bo Diddley

Though McComb has been endowed with innumerable talented musicians, one of the most recognizable names among them is likely Bo Diddley.

Ellas McDaniel (born Ellas Otha Bates, December 30, 1928 – June 2, 2008), known as Bo Diddley, was adopted and raised by his mother’s cousin, Gussie McDaniel, whose surname he assumed. In 1934, the McDaniel family moved to the South Side of Chicago, where he dropped the Otha and became Ellas McDaniel. He was an active member of Chicago’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, where he studied the trombone and the violin, becoming so proficient on the violin that the musical director invited him to join the orchestra. He performed until he was 18.

However, he was more interested in the pulsating, rhythmic music he heard at a local Pentecostal Church and took up the guitar. Inspired by a performance by John Lee Hooker, he supplemented his income as a carpenter and mechanic by playing on street corners with friends. Over the decades, Diddley’s performing venues ranged from intimate clubs to stadiums. The origin of the stage name Bo Diddley is unclear. McDaniel claimed that his peers gave him the name, which he suspected was an insult. Many believe it was a reference to the diddley bow, a homemade single-string instrument played mainly by farm workers in the rural South.

Diddley started on guitar at 12, when a family member gave him an acoustic model. He then enrolled at Foster Vocational School, where he built a guitar as well as a violin and an upright bass. His first trademark guitar was also handmade: he took the neck and the circuitry off a Gretsch guitar and connected it to a square body he had built. In 1958 he asked Gretsch to make him a better one to the same specifications. Gretsch made it as a limited-edition guitar called “Big B.”

His use of African rhythms and a signature beat, a simple five-accent hambone rhythm, is a cornerstone of hip hop, rock, and pop music. In recognition of his achievements, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987, the Blues Hall of Fame in 2003, and the Rhythm and Blues Music Hall of Fame in 2017. He also received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Rhythm and Blues Foundation and the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. He influenced many artists, including Buddy Holly, Elvis Presley, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Animals, and the Clash. Diddley is also recognized for his technical innovations, including his distinctive rectangular guitar, with its unique booming, resonant, shimmering tones.

On songs like “Who Do You Love,” his guitar style – bright chicken-scratch rhythm patterns on a few strings at a time – was an extension of his early violin playing, he said. “My technique comes from bowing the violin, that fast wrist action,” explaining that his fingers were too big to move around easily. Rather than fingering the fretboard, Diddley said, he tuned the guitar to an open E and moved a single finger up and down to create chords.

In 2006, he participated as the headliner of a grassroots-organized fundraiser concert to benefit the town of Ocean Springs, Mississippi, which had been devastated by Hurricane Katrina. When asked about the fundraiser, Diddley stated, “This is the United States of America. We believe in helping one another”.

Bo Diddley tribute in McComb, MS (photo by Brenda Germany)

Bo Diddley tribute in McComb, MS (photo by Brenda Germany)

Although Bo Diddley retired from performing in 2007 due to ill health, he was inspired to briefly sing in public for the last time when he attended the dedication of his Blues Trail marker in his hometown of McComb, Mississippi, in early November 2007. Bo Diddley died on June 2, 2008, of heart failure at his home in Archer, Florida. Garry Mitchell, his grandson and one of more than 35 family members at the musician’s home when he died said “The gospel song ‘Walk Around Heaven’ was sung (at his bedside; when it was done) he said ‘wow’ with a thumbs up, and said ‘I’m going to heaven.“

Diddley always believed that he and Chuck Berry had started rock ’n’ roll. That he couldn’t financially reap all that he had sowed made him a somewhat suspicious man. “I tell musicians, ‘Don’t trust nobody but your mama,’ ” he said in an interview with Rolling Stone magazine in 2005. “And even then, look at her real good.”

The Southland Music Line invites our readers to continue following along with us as we travel the Mississippi Blues Trail bringing you more discoveries about Mississippi, the birthplace of America’s music.

Click Here for more articles in the Mississippi Blues Trail Series at The Southland Music Line.

References:

Mississippi Blues Commission

Mississippi Magizine – Small Town Spotlight: McComb – Boyce Upholt

Mississippi Now – Mississippi Department of Archives and History

NYTimes – Ben Ratliff – Jun 3, 2008

.

Page Designed & Edited by Johnny Cole

© The Southland Music Line. 2020. All rights reserved